From Whence Came Thee

THE INTERNAIONAL OLEADER SOCIETY PRESENTS

The Oleander – From Whence Came Thee

by Elizabeth Head

A compilation of data with special recognition of the information published by F.J.J. Pagen (12). Program was given to International Oleander Society members at September 1999 meeting)

INTRODUCTION

From the first verse of my poem, you can see my curiosity about the history of the oleander:

Blossoms with the Past (34),

Perfumed air, brilliant hues

Cause me to wonder and to muse

What ship brought thee from afar?

What voice named thee oleander?

I shall attempt to answer some of these questions from my research and you will see that we admire and propagate a very ancient flower. The history begins with the ancient botanical explorers, collectors and scientific writers who are sometimes known as the plant hunters. (20)

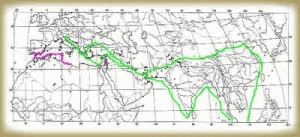

History

From the map you can see the early geographical distribution history of the oleander shown as black dots. (12) These are areas where it grows in the wild or where it was naturalized to the wild many years ago. It is widely cultivated and naturalizes very easily which makes it only sub-spontaneous in some of these areas.

PHOENECIA AND PHOENECIAN COLONIES

MARCO POLO TRADE ROUTES

It grows naturally in a wet habitat, well exposed to the sun. (12) You will find it on the banks and beds of streams and wadis that carry water during at least part of the year. It can grow in an altitude of 100 meters near the Dead Sea to about 2500 meters in the Atlas Mountains of North Africa. Its long roots enable the plant to tap water from deep sources. Thus, you find it all along the areas near the coast and on into Asia. Also, it is cultivated generally throughout East Africa. (36)

Research does not lead one back to the actual beginning when the plant that we now know as the oleander began to evolve and to take its place on the earth, but it can take one back in history to the time about 4000 BC. Of course, the oleander was not known by its current name, but scholars have been able to identify it as the plant we now know as the oleander. To begin with, H.W. Smith (15) in his book Man and His Gods mentioned that it was cultivated in the Valley of the Nile during the Old Kingdom Dynastic Period (3400-2475 BC)

1999 was the Jewish year 5760 and if you subtract 2000 you will find yourself in the time written about in the Bible about 3700 BC. Quoting from the Bible: On the 15th day of the 7th month, when you have gathered in the produce of the land, you shall keep the feast of the Lord 7 days, on the lst day shall be a solemn rest, and on the 8th day shall be a solemn rest. And you shall take on the lst day, a fruit of a goodly tree, date palm fronds, and a bough of a leafy tree, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the lord your God 7 days.” Leviticus 39-40 (6).

In reference to the four plants mentioned above, the Hebrew sages see” the 4 species as symbols of the historical move from the desert to the promised land.”(6) The oleander is one of 3 candidates for the leafy tree. The other two are the plane tree and the myrtle.

“Said the sages: ‘the ways of the Bible are pleasant,’ so it cannot be the oleander (because the oleander is known as a poisonous plant, and even though its branches do ‘cover the tree’s trunk’ and it is thick and leafy, it is impossible that the Bible-whose ‘ways are pleasant’-would command the use of a poisonous plant in celebrating this holiday.” (Sukka 32b) (6) (Neot Kedumin-The Gardens of Israel.)

Another possible name for the oleander in the Bible is the Rose of Jericho. The oleander is a sign of water and in the Book of Ben-Sirah-It is like the rose that was planted at the river.(21) The rose (vered) is a bush (rodon varon). The Greeks call it the Dafna rose because of the beautiful flowers and the resemblance of the leaves to a plant called Dafna found in Israel. It is called rodofne in the book, Psachim. Also, in a translation from this book is found-Because Moses sweetened the sour water with it, it was a miracle within a miracle, as the oleander was also bitter.”(21) In Holin, Mishna, the oleander is mentioned as an animal poison.

Finally, in Israel it is used to make temporary shelters for the Feast of the Tabernacles. (12)

Next, I will take us to the time 2900-1200 BC. The time of the Phoenicians. The oleander is reported to have been introduced to Western Europe by the early Phoenician colonists. (2) Phoenicia is on the map in the area of Syria, Lebanon and Israel of today. They were the first to send out explorers and establish colonies throughout the Mediterranean regions. (27)(38) They lived as early as 2900 BC but they did not become a great sea power until 1100 BC.(38) Phoenecia was one of the garden spots of the Roman empire and so it seems logical that they would also introduce familiar plants to their new colonies and outposts. (This could explain the areas of distribution around the shores of the Mediterranean.)

It is known that the Ancient Greeks maintained holy forests of oleanders and garnished altars with their blossoms to honor the Nereides, who were considered to be infallible guides.(12) The word Nerium could be derived from the Greek Nerion, which supposedly refers to the Greek Sea God Nereus and his daughters the Nereides. In Greek mythology Nereus was one of the old Men of the Sea, the son of Pontus (the High Seas) and Gaia (the Earth).(29)(5) His wife was Doris, daughter of Oceanus. He represented the elementary forces of the world and was considered a benevolent and beneficient God. The Nereids were sea deities numbering 50 or more and were said to personify the countless waves of the sea. One of these was Thetis, mother of Achilles. They were said to have lived in the bottom of the sea and have been pictured playing in the waves.

It has also been suggested that Nerion is derived from the Greek Neros, which means moist and refers to the wet places where the plant grows wild.(12 ) Dioscorides (b. c.AD40-d. c.90)(24) used Nerion to indicate the oleander and knew it as a plant growing wild near the sea and along rivers and sometimes cultivated in gardens.(12) He said the leaves could be used as a counter poison to snake bites.(2) In Greece it is known as Rhododaphne and it was used in funerals.

In 330 BC, Theophrastus (b. c.372BC-d. c.287)(28), a pupil of Aristotle, spoke of a bush with leaves like an almond and a red flower like the rose.(2) He knew it as Oenothera. He was known as the Father of Botany and 2, 330 years later, Greek words still name some of our flora. (32)

Cicero (106-43 BC) was said to have the oleander in the Roman Gardens.(12)

Pliny, an Italian (AD23-79), wrote many historical and technical works.(23) He gave directions on how to propagate by layering and by seed in his Historia Naturalis.(12) He said the Greeks called it Nerion, Rhododendros, Rhododaphne-but it hath not found a name with the Latines.(2) Only his 37 volume work mentioned above has survived and its only value now is to show the state of scientific knowledge at that time.(23) In Italy it is known as Lauro Rose, Leandro and others.

In Pompeii on the 24th day of August, AD79, Vesuvius erupted and covered Pompeii with a 23 foot thick layer of volcanic dust and pumice.(10) It has been under excavation since the 18th century and is 60% or more uncovered. It is now being restored in place. The oleander is the plant most frequently represented in the garden paintings on the walls of peristyle gardens.(12) A peristyle garden is enclosed by a colonade or at least on 2-3 sides. These murals made the small gardens appear larger. The oleander was usually pictured in an informal setting, growing in masses and forming a background for fountains, vases, and statues.

The International Oleander Society assisted with the Pompeii exhibit at the Houston Museum in 1991 and Kewpie Gaido and I took oleander plants to be included in the reproduction of the peristyle garden. (31)

Kewpie Gaido and Mary Joe Naschke POMPEII exhibit Jan .12, 1991, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Murals such as those in Pompeii were also found in the garden room of the Villa at Prima Porta built by Augustus for his wife Livia and in the auditorium of Maecenas in Rome. (12)

Pictured in the Horizon book of Ancient Rome is the area of The Forum, hub of Romes public life. (13) Here we see the Arch of Septimius Severus, and you will notice an oleander growing nearby and, also, in murals from a Roman villa in North Africa.

The Moors (in general, Muslims) of Mauretania, Northwestern Africa “attributed great magical virtue to The Sultan of the Oleander which is a stalk with 4 pairs of leaves clustered around it.” They also spoke of the wind in the oleanders which was said to make delicate voice-like music. (11)

In the 12th century, the oleander was one of the flowering shrubs together with the myrtle and the rose used by Arab gardeners of the Dar-al-Islam. (12)

In China, the oleander was said to have been in the gardens since the Middle Ages. (9) In 1299 a Treatise on Bamboo mentioned a bamboo-like plant in pots that was later identified as the oleander. Its first arrival was said to be from a sea route to Fukien Province in the South. Cultivating the oleander was the hobby of literary men who adorned their studies with cut blooms. (12) They liked the scent and elegant habit of the plant, and they chose it as an emblem of grace and beauty. Three characters were used to name it-mingle, bamboo and peach blossom -because the flowers resemble peach blossoms and the foliage the bamboo, (KIA TCHOU TAO). It was also used for medicinal properties. (22)

In the China of today it is said that at least one bush of a flowering shrub is to be found in every farmyard. (3) In every town, flowers are always on sale where food is bought, and flowers are very cheap to buy.

In the 15th century, the only variety known and cultivated in Europe was the common Mediterranean form, a single odorless pink to red blossomed plant. (12) In 1547, a single white was introduced into Italy. It had been found in Crete, near Camerachi on Mt. Ida. Crete was the home of the ancient civilization of the Minoans. (32) Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) was a Swiss doctor known for his systematic compilation of information on animals and plants. (25) He published many diverse works-one of which was Historiae Animalium. He never completed a similar one on plants but his notes and 1500 wood engravings of plants and their important flowers and seeds were used by other authors for 2 centuries after his death. In 1560, he mentions oleander in cultivation in Basel, Switzerland. (12)

John Gerard (1545-1612) was an English herbalist and author of The Herball or general historie of plants in 1597. (25) While studying in London he became interested in plants and created a garden. Both he and his garden became very popular, and people brought him plants and seeds from all parts of the world. In 1596, he compiled a list of plants in his garden and published it in 1597. It contained 1000+ species and was the first plant catalogue. He probably used the work of others with descriptions and wood cuts. His Herball was immensely popular and contained common and botanical names, descriptions of habitats, time of flowering, and uses and folklore. In 1596 in England, there were the red and white forms. (12)

Dr. Clarissa Kimber of Texas A&M gave the Society an interesting program at one of our Oleander Festival seminars. (8) Her doctoral student, Darrel McDonald, also has spoken to us several times. The field known as ethnobotany studies how plants have migrated with people around the world. She told us that exploring and colonizing nations established plant collecting and plant introduction gardens in their cities and in the colonial areas. These gardens were (a) staging areas for plants to be redistributed to colonies for agriculture (b) medicinal plants (c) growing out places for rare and unknown plants to be studied taxonomically and (d) parks for leisure.

From the 1500s on, the Dutch were keenly aware of the economic potential of food, spice and horticultural varieties. (8) The Dutch and French established way stations for new plants in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. These stations later developed into Botanic and Introduction Centers such as the ones established in Padua, Italy in 1545, in Leyden, The Netherlands in 1579, in Jardin les Plantes, France in 1635 and Kew in England in 1759. Also, in the New World in St. Vincent and Martinique in the Caribbean and Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

Oleanders have been grown in England for over 400 years. (2) Exotics such as the oleander found their way into English” hybernizing houses” by way of diplomatic couriers, merchant seamen and other travelers. (20) Nurserymen had paid agents at the docks whenever shipping made the Port of London. It is said that the plants in England were grown from seed brought from Spain (2) (colonized by the Phoenicians). For generations the oleander was a favorite plant of English gardeners and were grown in large tubs and planters. It was the favorite plant of sunrooms in 1596.

Nerium Bloom, India

In India, the oleander is considered a native of the western Himalayas and west to Nepal extending through Persia to the Mediterranean and also east to Japan. (33) Here mention was made of the hose in hose flower type. It is called Kaner by the Hindi, Karabi by the Bengals, and also Rose Bay. Oleander flowers are among those chosen by the Hindus to offer to the God Siva. They are also used in funerals. In India, flowers are believed to have great spiritual significance. Quoting from Flowers–their Spiritual Significance (30) “In fact, in all countries, flowers have been associated with religion and worship, with myths and legends. And to people all over the world they have been symbols of love and remembrance. A flower contains all the elements of nature…air, water, fire, earth and ether. Apart from its beauty of form, colour, fragrance and texture, there is something more-an indefinable, subtle and mysterious quality about it.” In the words of The Mother, the oleander is a flower in the Clock of Nature. You will find it at the hours between 4 and 6 and its spiritual name is Quiet Mind for the single white flower and Perfect quietness in the mind for the double white.

“We have been sent the book mentioned above by member R. Haresh of India and also have one called Red Oleanders, a play by Indian author Tagore. (17) whose heroine Nandini was symbolized by the oleander, interpreted as frailty or the red badge of courage.

It has been recorded as being introduced to Bermuda in 1790. (14) The English had instructed the Governors of such colonies to make the islands beauty spots of the world. Some historians trace the oleander to the South Sea Islands. (7) A captain of a sailing ship is said to have brought it to the West Indies Islands where it was known as the South Sea Rose.

Spain is a country with an old and rich horticultural tradition. (18) The Spanish were expert gardeners who adapted freely from other cultures. They traveled widely and established colonies in all of the Gulf Coast States of the United States. In 1565, the oleander was brought to Florida by early Spanish settlers. (12) The purpose of these colonies was to be military outposts first, and agricultural outposts second. (18) The Spanish knew the oleander as Adelfa, Alendro, or Laurel Rosa. Their influence on American colonial gardening remains strong in the Southern United States today.

In 1683, Van Rheede Tot Drakestein introduced a single fragrant light pink variety into Europe from India. (12) The double pink form was introduced by Beverningk from Ceylon. In 1689, an Indian oleander with variegated double flowers was brought to Leiden.

Tournefort (1656-1708) was a French botanist and doctor who went to Asia Minor and Greece. (28) He wrote his Elements de botanique. He was a pioneer in systematic Botany-he introduced the single Latin name for the genus of a plant, followed by descriptive words for the species. In 1688 he became a professor at the Jardin de Plants. In 1700 he gave the oleander the official genus name of Nerion.(12)

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was a Swedish naturalist and doctor who provided biology with a descriptive procedure, a standardized terminology and nomenclature and ways to handle and organize systematic information. (26) He introduced the BINOMIAL NOMENCLATURE system. Before, as mentioned above, you had a Latin or Greek generic name followed by descriptive terms. These differed greatly from person to person and created a great chaos. He produced his Speciesplantarum in 1753. In this work he gave a classification of the genera defined on the basis of an internally consistent set of criteria. He based this on the number of stamen or structure of the ovaries. He introduced a fixed descriptive terminology for botany and zoology and named the genus Nerium in 1737. (12) We know the oleander to this day as Nerium oleander L. which stands for Linnaeus. He studied medicine and natural science. (26) In 1735 he went to Harderwijk University to become acquainted with Dutch botanists and to find a publisher. He published his Systema naturae and met George Clifford, a wealthy banker who hired him to describe his collections of plants and animals on his estate. Here he produced the Hortus Cliffortianus and also Fundamenta botanica and Genera plantarum. He became a Professor of Botany at the University of Upsala.

A pupil of Linnaeus, Daniel Solander (1736-1782) sailed with Joseph Banks as Botanist on Capt. Cooks first voyage of exploration in The Endeavor from 1768-1771. (16) He named the oleanders he found in India as Nerium odorum and in earlier times you will find those he named as Nerium odorum Soland, a second species. He became keeper of the Natural History Department of the British Museum, London.

Philip Miller (1691-1771) also named the fragrant Indian varieties as Nerium indicum Mill. (16) Miller was an English gardener and botanist who was curator of the Chelse Physic Garden and author of the Gardeners Dictionary in 1731. Present scholars have now determined that the genus Nerium is monotypic and no longer use these other two names for species. (12)

Also in the 1748, Weinmann introduced a variegated leaf form of the Mediterranean single pink and Indian oleander with red double flowers; in 1789, Aiton mentions a double form of both the Indian and Mediterranean varieties. (12)

In 1812, a yellow, single form of the Indian oleander named Nerium flavescens was discovered by Di Spio; in 1840, Bosse mentions 36 varieties and in 1849, 58. (12)

In France, a reference to an oleander cultivar appeared in a nursery catalogue in 1799. (4) We later find Vincent van Gogh painting the oleander in 1888-Majolica Jar with Branches of Oleanders and another in Arles. (37)

Van Gogh’s oleanders

The Index kewensis, published in 1894 by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, lists species under their genus and details whether or not they are true or misnamed species. This index helped me reply to an inquiry about a Nerium tinctorium which was supposed to be used to make a beautiful blue dye. It had been incorrectly called a Nerium and was instead a Wrightia species.

In 1898, Claud Sahut in Montpelier, France, offered 170 cultivars growing in his nursery. (12) He listed the flower type with superposed corolas in 1868. In France, they are known as the Laurier, laurelle, or the Fleur de St. Joseph. Today in France, the Filippi nursery catalogue of Clara and Olivier Filippi lists 112 varieties. (35)

Cornelius Weygandt in his book, A Passing America, describes the oleander amongst the early colonists. (19) His mother's family had come to the United States on the Mayflower. As a background he writes that in Britain and Germany the oleander was not an uncommon houseplant. Consequently, the oleander was found everywhere among the Pennsylvania Dutch, both the rose, double, and the white, single. Bottles with cuttings would hang in the back sheds. He quotes-” The loss of our old double rose plant of 2 score, and more years took a measurable joy out of my life. There is a satisfaction difficult to express in the possession of a plant that had come to you from your people. It is not exactly the pleasure you have in an heirloom, but in something you value because it ministers to a sort of pride you have in the well-being of the stock from which you are sprung. The plants that your parents cared for are a living link between you and them. The very perishability of the plant makes it dearer………So when we lost our old oleander, I felt in a minor way that sort of helplessness we all feel in the presence of death.”

Scholars have mentioned that the oleanders were favorite plants in Jeffersons time. At restored Monticello, large plants are wintered over in the old earthen cellars.

William Bollaert in his book on Texas (1) mentions New Orleans in 1842-In New Orleans and its vicinity, vegetation is most prolific in the flower gardens. Exotics such as we have under glass in England are to be seen in great variety in the open air, particularly, the Nerium oleander forming groves.

Oleanders came to Galveston on a trading ship from Jamaica. (7) Both the double pink and the single white as mentioned in A Passing America arrived here in 1841. It is also probable that others were brought here from New Orleans where groves of oleanders were already flourishing. In interviewing older Galveston residents, I was told that during the early 1900s many cuttings were brought back from trips to Europe.

The oleander has thrived in this island city of Galveston which is now known as “The Oleander City.” In 1967, oleander admirers organized and incorporated the National Oleander Society and began to preserve the many varieties that had developed here. In 1987, the original name was officially changed to the International Oleander Society since the beautiful plant is known and admired on a worldwide scale as you can see from its history.

Members have sent us pictures from all over the globe which we share with you on Around the World.

We would like to acknowledge Mrs. Elizabeth Head for her hard work and determination in compiling this article. Mrs. Head is the driving force behind the International Oleander Society and her dedication to the promotion of the oleander is admired by all its members.

Email the author of this article fhead@msn.com

Folklore

Folklore

Historians believe the oleander is native to the Mediterranean region, traveled with explorers to the South Pacific, then found its way to the West Indies. Early in the British occupancy of the West Indies, Colonial governors attempted to make the area a fairyland by cultivation of choicest fruits and flowers from all over the world, adding to the beauty of the native flora. Masters of the Southward voyaging ships were charged with collecting seeds and cuttings for transplanting.

Responding to this charge, a captain returning from the South Sea Islands brought some oleanders which came to be known as “Sea Rose” or South Sea Rose.

Throughout the years, Galvestonians and others have used their imagination to produce fanciful legends as to the origin of the name “oleander” and the plant. Early Galveston citizens thought that it was a kind of olive bearing bush; this confusion with the olive tree whose Latin name is Olea may have been the source of the name. It is also surmised that the name oleander came from a corruption of the Latin name for rhododendron with which it has also been confused.

In keeping with the Mediterranean origin of the oleander, one legend has it that oleander in Greek mythology means romance and charm. A beautiful Greek maiden was wooed by Leander who swam the Hellespont every night to see his beloved. One night he was drowned in a Tempest. Wild waves dashed his body against sharp rocks and left him lifeless on the white sands. Here his lover found him as she walked the shores calling “Oh Leander, Oh Leander. "The beautiful flower was clutched in his hand. She removed it and kept it has a symbol of their love. Magically it continued to grow and from this symbol of everlasting love came the beautiful and abundant oleander.

The biblical Rose of Jericho is thought to refer to the oleander and there are Christian legends concerning its origin. In Tuscany, Italy, the oleander is known as St. Joseph’s Staff which was said to have burst into flower when in the Angel announced that he was to marry the Virgin Mary. In 1915, Charles M. Skinner published another legend concerning St. Joseph and the oleander in a local paper. It seems that a poor but lovely Spanish girl lay ill of a fever. Her mother tried all that her meager resources permitted to cure her daughter, but to no avail. Exhausted by her desperate efforts, the mother fell to her knees to pray to St. Joseph to spare her child. When she arose, the room was filled with a rosy glow from a figure bent over the girl.

The handsome Prince Neptune won her heart and everyone in the kingdom was overjoyed. a date was set for the waiting and the day dawned clear and bright. The guests were assembled for the ceremony when suddenly the son of Witch Hurricane appeared.

He was wildly angry and furious at losing the Princess. As he advanced, blackened and distorted with rage, the fairy god mother of the Princess intervened and waved her wand, transforming members of the wedding party into beautiful oleanders and stately palms. Prince Hurricane and his mother, the Witch, tore around all that day and the next without finding the Princess and they finally departed. Another legend involving the buccaneer, Jean Lafitte, in the establishment of oleanders on Galveston Island, is less romantic. In the pursuit of his pirate’s craft, Lafitte had attacked a Norwegian schooner and killed all the passengers except for one man was clinging to a beautiful flowering plant. His name was Ole Anderson. Lafitte saved him and made him his gardener, calling him Olea Ander. He later honored him by calling his flower by the same name. Two traditionally uses of the oleander come from different parts of the world. In India, Hindu mourners place oleanders about the bodies of dead relatives using the blooms as funeral flowers.

OLEANDER CULTURE

Here is some helpful information from our handbook regarding Oleander Culture:

Plant Selection– For optimum results with oleanders, variety selection is a key factor. After identifying the variety best suited for the intended site, attempt to observe plants whenever possible prior to purchasing. Avoid plants labels as double white, single red, etc., and select only those that specify exactly which variety is offered for sale. This ensures that the small plant purchased will develop into the matured specimen intended for the site. Desirable plants have dark green leaves, the thick stems, and appear dense and bushy. Avoid plants with broken branches, yellow or necrotic. leaves, wounds on stems, or those having weak spindly stems. Examine for oleander gall and insects, especially aphids and mealy bugs. Containerized plants should not be pot bound, i.e. have overgrown root systems consisting of dense roots completely encircling and obscuring the growing media. Instead, select plants that continue to retain the root mass intact when removed from the container, but also allow for some visibility of the growing medium.

Site Analysis & Preparation – Oleanders are adapted to a variety of sites within the landscape but do best in full sun locations. Plants grown in partial shade will produce flowers, but less profusely. Although sparse blooming results from planting in dense shade, oleanders will survive in such areas. A wide variety of soil tides and moisture regimes are tolerated by the oleander, from dry sandy soils to moist clay soils. Also, they are tolerant of soils with high levels of salt content. Oleanders make excellent wind breaks, but damage sustained by flowers during high winds can destroy both open blossoms and flower buds. Coastal plantings incurred salt damage to leaves in the form of leaf tip browning. Researchers (Hagiladi et al. 1989) reported the oleander to be moderately salt sensitive and that significantly less leaf scorch occurred whenever overhead sprinklers were activated during high winds. When considering plant location within the landscape, consult with local utility companies for location of the underground pipes, wires, etc., whenever applicable. Review city ordinances concerning planting on public right-of-way is along sidewalks and streets, since this may directly affect maintenance requirements imposed by the restrictions on plant height. For instance, the Galveston City Code, Section 34-6, on intersection visibility forbids shrubs within the public right-of-way > 30 inches in height and within 20 feet of curves at the intersection of public streets or intersections of public traffic. The provisions of this section do not apply to “trees or other plant species of open growth habits which are not planted in the form of a hedge, and provided that such may be trimmed to the height not less than eight feet above the adjacent sidewalk….”

Pre-planting Care – Knowledge of growing conditions for plants shipped from other than local nurseries are desirable for acclimating plants to local environments. Differences in temperature, moisture, regime, light intensity, fertilization, and other environmental variables can have adverse effects, such as leaf drop and shock, on recently installed plantings. Whenever possible, gradually introduced plants into drastically different growing conditions over a period of several days to weeks. After receiving plants, keep them moist and protected from temperature extremes in preferably a shaded area while in holding, arrange plants close together to reduce transpiration losses and help keep them erect during windy conditions.

Planting – After determining exactly where to plant in the landscape, dig a hole for each plant two to three times the diameter of the container or root ball. This allows for back filling soil into the planting hole with a minimum of disturbance to the root mass. The hole should be only deep enough to keep the plant at its original level as in the container or as in the ground for field grown stock. Balled and burlapped specimens should be handled very gently to avoid disturbing the roots and, whenever possible, refuse to accept, for installation, plants with broken root masses. The same applies for container grown plants, with the exception of pot bound plants. In these cases, it is recommended to split the root mass from the bottom upwards to one third 2 1/2 of the height, to promote spreading of the roots. Soil used to back fill the planting holes may be the original soil onsite or some similar soil. Some authorities recommend adding one-third organic material, such as peat moss, especially on sandy sites, to temporarily increase the water capacity of the soil. Plants should be thoroughly watered soon after installation. Creation of a burm or small dike 2-4 inches in height surrounding the planting hole will serve as a reservoir and facilitate watering the plants. Frequent misting of foliage, especially during hot or windy conditions, will help prevent excessive foliage desiccation. Pruning newly transplanted oleanders is not necessary under circumstances where the plants will receive sufficient water through irrigation or rainfall. Whenever water stress is a likelihood, removing one third to 1/4 of the foliage, may increase chances of survival. Remove growth that easily desiccates, such as young growing tips and other tender parts. Providing support for standard or tree form oleanders is often practiced helping keep plants erect. This is usually accomplished through guying or two types of staking (see picture). Anchor staking, he is used on upright plants to keep the root mass in-place until the roots have grown sufficiently into the ground to support the plant. Usually, standard forms have trunks too weak to provide support for the canopy and they should be support staked whenever possible for easier maintenance. Very large tree form specimens may require guying, where usually three guidelines are extended from the trunk to anchors driven into the ground.

Planting Time – The proper planting time is just after bloom time and no later than September, or you will be cutting off next year's blossoms. Some oleanders don’t want to stop blooming, so you’ll just have to grit your teeth and cut off the flowers if the plant is in need of pruning. If you are starting off with a new plant or you want to completely redo a plant that has gotten out of hand (a leggy one for instance), you may wish to give up the first year’s flowers and prune all spring, summer and early fall. (Quit pruning when the weather gets chilly, or you may kill the plant.). You will be rewarded the following year for your abstinence. Oleanders are known to survive with a minimum of care when planted into the landscape. However, the proper treatment of plants before, during and after planting helps to insure increased survivability, faster establishment and subsequent growth.

Care

Water Requirements – Established plantings of oleanders are considered tolerant of ordinary drought conditions, with most plantings on Galveston Island receiving little or no supplement to natural rainfall. However, drought stress does have adverse effects, such as causing a reduction in growth rate and flower production. Supplemental watering at the rate of 1-2 inches per week, during dry weather conditions, promotes continuous flowering and constant growth of plants.

Fertilizer Requirements – As in the above case of water requirements, established plantings of oleanders generally do not require fertilization, but plants may respond favorably when fertilized by increasing growth rate and flower production. Signs of unfavorable soil nutrient levels for oleanders include light green, often small leaves, short internodes, lack of terminal growth of stems and sparse flowering. A general recommendation can be used where two pounds each of actual nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium are applied for 1000 square feet area occupied by roots of the plants. The first application made in early spring followed by a second application made in early fall. Oleanders growing in lawns that are properly fertilized generally will not require supplemental fertilization.

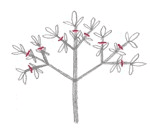

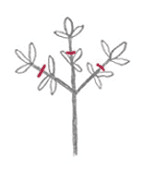

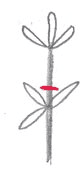

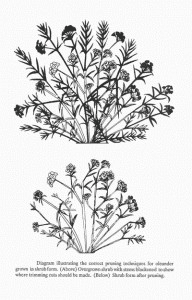

Pruning Tips: – Oleanders are very easy to prune. Pruning will reward you with a strong, healthy plant with lots of bloom. Here is how the procedure goes: Oleanders should be cut back just above the leaf nodes. This is the section where three leaves come out of the branch.

By cutting it here, you will be forcing new branching at each of the leaf nodes (joints). You will therefore get three new branches coming from the section which once had three leaves. By letting these new branches grow a little bit and then pruning them also (at the leaf nodes), you will again force new branching to occur at these points. By doing this, you will again increase the branch threefold. This is how you get round, bushy plants. Remember, the location of you first pruning should be low on the plant to allow a good base structure for all the future branching. See sketch. Now…for an added bonus, at each new branch tip, you should get a flower cluster…therefore, by having more branches, you will also get more flowers.

Why Prune? The main reason people prune their oleanders is to shape them and force more branching – giving more flower clusters.

When should I prune? The best time to prune oleanders is around September into early October. Pruning any later will cut off the Spring growth.

Does the flower bloom on old wood or new wood? Flower clusters appear at the tips of new wood.

How much can I trim my plants? Oleanders are very strong and can take a good amount of pruning. Don’t be afraid to cut them back to whatever base height you may want – especially if you feel they’ve lost control!

Propagation – It is very easy to propagate from oleander cuttings. There are two good ways…one says to use the hard wood, while the other says that tip cuttings are the best. You can use either way and still be successful. Make your cuttings about 6 inches long each and remove the lower leaves. The location of the bottom three leaf nodes is where your roots will start, although they will progress elsewhere. Cut the remaining upper leaves to about one inch long. You can place these in water by themselves or put in a small twig of willow – which acts as a stimulator - long with the cuttings in the water.

After the roots grow to between one and two inches long, transplant into some good draining soil. Keep it moist, but not wet, and in a mostly sunny location. Another method is to dip the bottom end of your cutting in ROOTONE and plant it in some sand. Either method should bring results in about two weeks. In about a year, these will have grown to gallon size and continue from there. Don’t forget to prune them after they reach the gallon size, so you get the shape and structure you want. As the old saying goes, if at first you don’t succeed… It will work!

Potted for Centuries

(Growing Oleanders in Northern Climates)

James Nicholas

I first encountered oleanders as a 14-year-old on a trip to Hawaii. Having been a gardener and nature bum since about the age of 6, I identified them from the memory of an illustration in a guide book and (with what now seems like a strangely well-developed taxonomic sense) also recognized them as members of the Apocynaceae or dogbane family.

Always enjoying a challenge, especially if it meant sneaking around the system, I swiped cuttings with my pocketknife, stuck them in a glass of water for a few days, and managed to smuggle them to the mainland, where they rooted and grew. Some hibiscus cuttings which I also, uhhh, borrowed on the same occasion also rooted and grew successfully; years later, I would rediscover the unforgettable plumeria and learn to grow, flower, and propagate it in the so-called temperate zone, where the temperature can range from 3 to 103 F (-16 to 39 C).

Some of my friends in the International Oleander Society have expressed surprise that oleanders can be grown up North, or even that Northerners know about them at all. In fact, the oleander has been a favorite container plant in Europe for well over four hundred years, and is the number one most popular pot plant in Germany today. Friends and acquaintances of mine from France, Germany, the Netherlands, former Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania all have vivid childhood memories of Mama’s oleander back in the homeland. In the area of Central Connecticut where I now live, there is a very large Italian population and it is very common to see one or several oleanders growing in huge tubs in front of the house; on some streets it seems that every third household has a collection of them! So, from the perspective of a Northerner, it’s very normal to grow oleanders in pots, just like geraniums; the weird thing is seeing them grow in the ground!

Oleanders, then, are obviously easy to grow as container plants, even in Yankee territory. There are certain odd things about their original habitats which are both interesting to know and helpful for nunderstanding the cultivation cycle, but oleanders are definitely both forgiving and rewarding for the inexperienced container gardener. In fact, cultivating oleanders is more like arts-and-crafts than it is “real” gardening! I hope the following tips will make them foolproof for those who would like to grow them, for example, in zones 5 and 6.

But aren’t oleanders poisonous? Sure they are; so what! You aren’t planning to eat your oleanders, are you? Those of us who live up North should know that rhododendrons and azaleas, which we all grow and love, are as bad or worse than oleanders in the toxin department. So is English ivy. Daffodils and lily-of the valley will send you straight to Hades, too, not to mention all those houseplants: poinsettias, dieffenbachias, philodendrons, Christmas peppers, and peace lilies (there’s a reason they’re called peace lilies!). Your animals are too smart to munch on them, and you and your children should be, too.

Learn to root cuttings: Your first oleander may come in the form of a cutting given to you by a gardening friend, or stealthily removed from a potted specimen plant or a hedge, as mine was! Keep this in mind as well: even in the North, a vigorous grower such as Pink Beauty, Ed Barr, or Scarlet Beauty/Emile Sahut will grow a foot or more in height during a summer outside. Eventually, you will want to prune to keep the plant under control and perhaps to start over again with a conveniently-sized small pot plant which is ready to bloom. The best time to root cuttings is from late spring to midsummer. Take a tip cutting 8-10 inches (20-26 cm) long, or stem cuttings 5-8 inches (13-20 cm) long from the middle or lower sections of the branch. Each cutting should have at least two sets of leaf nodes. Pull off all but the top whorl of leaves, and trim those to about one inch from the stem to reduce moisture loss. Most varieties will root successfully if simply put in a glass of water. However, the plants will actually get off to a healthier start if the cuttings are rooted in a solid medium. Roots formed in water tend to be thin and fragile, as they encounter no resistance while emerging. In addition, the stems are likely to be frequently jolted and moved, leading to root breakage, as the water is changed (which it must be every couple of days in order to prevent the development of a population of harmful bacteria)

The plant then requires a period of adjustment after being potted up. By contrast, roots formed in a solid medium are thick and strong, meaning that the newly-potted plant undergoes little or no transplant shock. I have found that perlite yields the best results of all rooting media, being light, sterile, moisture-retentive, and quick-draining. And, as Richard Eggenberger points out in The Handbook on Oleanders, the perlite grains cling to the root mass upon removal, helping to form a stable, solid clump which is much less susceptible to damage during the transplanting process.

Cut the tops off of plastic milk or juice jugs, stab 8-10 drainage holes in the bottom with a penknife, and fill them with perlite. After watering the medium and allowing it to drain, moisten the cuttings, dip them for most of their length in Rootone, shake off the excess, dig holes with your finger or some similar implement, and plant the cuttings so that they are buried for most of their length. (Several cuttings may be placed in a single container) Then water again, let the container drain, and place it in a warm place away from direct sun. Keep the medium just damp; never wet!

Pinks and whites (perhaps being genetically closest to their original wild ancestor, the Mediterranean single pink) are usually the quickest to root; “Ed Barr” will generally be putting out roots in five or six days! Red cultivars seem to be consistently slower, but will become equally vigorous plants once established. Cuttings will often start producing little green shoots from the leaf scars in a matter of a week or two. Don’t be fooled; their roots, presuming they have formed at all, are not yet strong enough for them to be repotted. Do not be in a rush to remove the cuttings from the medium; they can stay in the perlite or sand for a good long time as long as they receive sufficient water.

Instead, bring them outside to gradually accustom them to the sunlight, increase the amount of water given, and let them grow a good “mop” of leaves. To remove cuttings from perlite or sand, immerse the container in a bucket of lukewarm water, let the water soak into the medium so that it becomes a semiliquid, and then reach in with your fingertips and gently tease the cutting out. (Thanks are due to Jim Little, the eminent Hawaiian plumeria grower, for this tip).

Use the right soil mix: Oleanders will grow in almost anything, but it helps to get them off to the best possible start by giving them a suitable potting medium to encourage a healthy root system. In their native habitats (the Mediterranean, the Middle East, India, and subtropical Asia) oleanders typically grow in sandy soil where there is abundant ground water, or where there are periods of flooding and then draining. John Houghton, an experienced grower of tropicals in Parsippany, NJ, suggested the following mix, and it works wonderfully for oleanders, jasmine, and many other tropicals as well: 8-9 parts (by volume) of a soilless potting mix, 1 part sand, and 1 part perlite. A quick-draining mix is more crucial in the North than it is in the South.

Don’t hesitate to give oleanders a generous amount of water when it’s hot (especially while they’re flowering), but when temperatures cool down at night, it is a very good idea to play it safe and let the mix get somewhat dry between waterings.

Use the right pot: To avoid danger of root rot, I recommend potting up new cuttings in relatively small (6 inch/ 15 cm) clay pots, because of the porosity of clay. If the plants are willing, try to keep them growing through the winter (or as long as you can) their first season so that they build up really strong root systems. Once that hurdle is passed, the danger of losing them will be minimal. As they grow larger, you may repot them in lightweight 8-10 inch (20-26 cm) plastic pots.

Using lightweight containers is especially important in the North, as the plants will have to remain easily movable (see “Build muscle tone”, below).

To avoid having plants blow over in the wind, you may either sink the pots partially or completely in the ground during the summer, or plant in square containers, which have more stability than round-bottomed pots. My largest plants are in 10-12 inch (26-30 cm) square, terra-cotta colored plastic containers which cost no more than $6 at Home Depot or Lowe’s. Make sure to punch plenty of drainage holes in the bottoms before potting up the plants!

Bake in the sun: Intense light, along with generous fertilizing, is the key to producing flowers. When setting plants outside in the spring for the first time, give them only about 45 minutes to an hour of direct sunlight the first day; add a half hour each day. After about a week, they’ll be ready and willing to take full sun all day. IMPORTANT: Even though oleanders enjoy a well-deserved reputation for being drought-resistant, this applies only to oleanders in the ground. They have a high water requirement in the summer, and will need water standing in the saucer during hot weather. If the plants are allowed to dry out or even wilt, flower size will diminish quickly and drastically, and the plant will quickly shed its lower leaves as a measure to counter the stress of water loss. Repeated stress of this kind may leave the plant vulnerable to attack by disease or insects (especially scale).

Keep ’em stunted! Oleanders grow large very quickly, even in the North. By using a fertilizer low in nitrogen and high in phosphorus (a “blossom booster” type), you will discourage excessive stem growth while encouraging blooming (and therefore branching).

But feed ’em well! In order to maximize flowering without encouraging a lot of stem growth, use a fertilizer with a super-high phosphorus index (the middle number of the three should be in the 50’s). Super Bloom, Peters Root ‘n’ Bloom or Blossom Booster, and Miracle-Gro Bloom Booster will all do the trick. I also supplement with a special time-release fertilizer: Tropical Bloom or Stokes’ Plumeria Fertilizer, though in some years I have been very lazy about this, and the plants did fine anyway. All fertilizing should cease by about the end of August; this will discourage the production of tender new growth which might be injured by cold autumn temperatures.

Build muscle tone: grow oleanders! One good reason for trying to keep the size of the plants under control and for using lightweight containers is that you might be bringing them inside and outside a fair amount toward the beginning and end of the growing season. Oleanders enjoy a long season of warmth and intense light; I try to put them outside on every warm day in early spring, bringing them in when cools down. Similarly, I try to take advantage of every warm autumn day to give them additional sun, even though it means they need to be carried back inside when there is a threat of frost.

Beddy-bye: There will come a point when the plants need a rest from their long season of blooming. The standard sources state that as long as the temperature is kept above freezing, the plants will be fine.

However, to avoid loss from root- or stem-rot, it is important to reduce watering to a minimum. The cooler the temperature, the less water and light the plants will need; keep them on the dry side. An unheated, bright porch or sun room is ideal, provided the temperature remains above freezing. Oleanders can also be overwintered at normal room temperatures. The warmer they are, however, the more light and water they will need. When you notice new, shiny, light green shoots emerging from the tips of the branches in the spring, it’s time to give them warmth, sun, increased water and fertilizer.

Minor challenges: In the house, oleanders tend to attract the unwelcome attention of spider mites, which spin fine webs on the leaf surfaces and give them a “cornmeal-speckled” appearance. I recommend misting frequently to keep the humidity up and to discourage mites. Keeping the air flow moving and opening the windows on frost-free days is also a good idea; for you as well as for your plants.

Green or orange aphids frequently appear and can multiply rapidly under warm conditions; check the plants often. I squish them with my fingers; the more squeamish may prefer to rinse them off with a mild soap or insecticide solution. When aphids attack a plant outdoors, ladybugs will generally find them very quickly and feast on them; however, even a ladybug can only eat so many aphids, so be vigilant and remove them as you see them.

Occasionally whiteflies are a problem; use a houseplant insecticide and follow directions. Even better are the mechanical traps made of yellow sticky paper which are both very effective and completely non-toxic. (I hate to spray poisons and almost always try to shower off, sponge off, or pick off any pests).

Scale insects are the worst pest of oleanders indoors but in my experience only attack plants which are already weakened by stress, especially due to water loss or mechanical injury. Good cultivation is the best prevention. If the plant has only a light infestation, try scraping the scale off manually (check the undersides of leaves, especially along the midribs). If the infestation is more serious, you will have to resort to an insecticide.

About the most serious pest that I have dealt with, however, is the big banner-like tail of Sparks, my handsome shepherd-collie mix; in moments of intense doggie joy, he has occasionally knocked over cuttings in 6″ pots, with no permanent damage done.

If you become the victim of your own success: you’ll wind up with monster plants. I keep my potted oleanders, even the tallest-growing varieties, no taller than 3 or 3 ½ feet high, through the use of low-nitrogen fertilizer and continual pruning. As the older branches become too tall, you may safely cut them back to a point about ½ inch above the first, second, or third set of leaf nodes from the base.

Generally, within a week you will see three branches emerging from the leaf scars directly below the cut. These will fill the plant in beautifully and should bloom the following year. Keep in mind that oleanders bloom on branches which are a year old or older, so if you are not prepared to sacrifice a lot of blossoms, cut back only a very few overly tall or unattractive branches at a time. For your shrub’s optimum health, do not remove more than a third of the foliage at any time. If you decide to prune a branch in late spring or early summer, you can use your new-found expertise in propagating to confidently take cuttings, and you can enjoy PORTABLE little blooming oleanders no more than a foot and a half high and have a huge supply to give away to gardening friends. So, give the “Gift” (German for “poison”) of oleanders.

Get growing!

Varieties

Pinks

Pinks

Salmons

Salmons

Reds

Reds

Whites

Whites

Yellows

Yellows

Special Varieties

Special Varieties

History of the Oleander in America… By Way of Galveston

History of the Oleander in America… By Way of Galveston

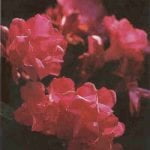

The first Oleanders came to subtropical Galveston in 1841. Joseph Osterman, a prominent merchant, brought them aboard his sailing ship from Jamaica to his wife and to his sister-in-law, Mrs. Isadore Dyer. Mrs. Dyer found them easy to cultivate and gave them to her friends and neighbors. The familiar double pink variety that she grew has been named for her. (Picture on right) Soon these new plants were growing throughout the city.

As early as 1846, note was taken of the yards in Galveston with oleanders and roses in full bloom and the contribution they made to the beauty of the city. Oleanders flourished in these early days of the city and were able to withstand the subtropical weather, the alkaline soil, and the salt spray. Therefore, it was logical for oleanders to be chosen as one of the predominant plants to be used in the replanting of the city following the destruction of the 1900 hurricane and grade raising that covered the existing vegetation with sand.

Concerned ladies of the city soon organized the Women’s Health Protective Association (WHPA) with the mission to beautify the island and improve the health conditions of the city. They planted along Broadway, the entrance to the city, and on 25th Street, the path to the beach front, and in a few years, oleanders made a spectacular display of blooms for citizens and visitors. Although the name of the WHPA was changed to the Women’s Civic League, planting continued for many years up and down city streets, in parks, in yards, around public buildings and schools and soon the whole city became a garden of oleanders. As early as 1908, an editorial in the Galveston Tribune observed that the oleander was emblematic of Galveston and that people came from all over to see them. In 1910, The Galveston Daily News also reported that Galveston was known throughout the world as “The Oleander City” and in 1916, an article named it one of the most beautiful cities in the South.

Through the pollination of the two original Galveston Oleanders, ‘Mrs. Isadore Dyer’ and ‘Ed Barr’, many hybrids have occured throughout the century. Many of these were distributed all over the United States and, today, are growing everywhere the climate is amicable. Today, corals, yellows, reds, pinks and whites in singles and double forms are found in the warmer climates of America.

The International Oleander Society

In May of 1967, through the vision of Maureen Elizabeth ‘Kewpie’ Gaido and Clarence Pleasants, the National Oleander Society (later to be changed to the International Oleander Society) was born. Inspired by Clarence Pleasants (known as ‘Mr. Oleander”) who’s love of this flower he shared with everyone; Kewpie promoted the oleander all over the world. She corresponded with, then Governor of California, Ronald Regan in 1971, after finding out that he had designated many miles of freeway to oleander plantings. She sent him many plants and cuttings in the process. Kewpie also talked with Lady Bird Johnson concerning her own promotion of the oleander around Texas.

Clarence Pleasants saw his first “Oly Andys” in Virginia as a boy and was taken by them and decided to dedicate his life to this beautiful flower. He attended a segregated two room “black only” school until the seventh grade since there were no other grades beyond that point.

He studied under Fredrick Heutte at the Norfolk Botanical Garden in Virginia for over twelve years. In his quest for knowledge of the oleander, he wrote all over the world looking for information on his favorite flower. In his quest he found out about the ‘Oleander City’, Galveston, and decided to take trip here. He would eventually move here on July 1, 1961 to be close to the land of the oleander.Elizabeth Head, society executive vice-president, who was also taken under the spell of Clarence Pleasants’ charisma and lure of the oleander, called him the “soul” of the Oleander Society.Today, the International Oleander Society has members all over the world. From France to Japan, the love of the oleander continues to spread. The society promotes this lovely plant through publications, educational projects, festivals and community services which include grants and scholarships. If you are interested in joining us, we would be more than happy to share our fun and knowledge with you. Taken from the books THE HANDBOOK ON OLEANDERS by Richard and Mary Helen Eggenberger

Click Here for Global Oleander History “From Whence Came Thee” by Elizabeth Head

Oleander in Ancient Times

Oleanders were found not only in ancient Greece but in Roman and Chinese gardens as well. “In China the cultivation of Oleanders was a hobby of Literary men who adorned their studies with cut Oleander blooms,” Pagen recounts in his book.

Due to the preserving layers of volcanic ash from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, we know that Oleanders were also grown in the gardens of Pompeii. They were the plant most often painted on Pompeian murals (circa 79 A.D.) and were usually found represented in informal settings as background plants or mass plantings in the unique, traditional garden wall paintings whereby the Pompeians created the illusion that their gardens extended far into the countryside.

The Hebrew holy text The Talmud mentions the Oleander numerous times, especially in the Mishnah, the first part, compiled around 200 A.D.

Toxicity

Toxicity

INFORMATION ON OLEANDER TOXICITY

Most importantly – If you, or anyone/thing else, believes they have been in contact with any poisonous materials, contact your local Poison Control Center.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers has a great website – www.aapcc.org – with information about all types of poisoning.

For the Galveston Area, the Southeast Texas Poison Control Centers (STPCC) website is www.utmb.edu/setpc.

To contact STPCC:

Mailing address: UTMB, 3.112 Trauma Building, Galveston, Tx 77555-1175

Emergency Numbers: (800) 764-7661 (TX ONLY) and (409) 765-1420

Animal Poison Control Center – www.napcc.aspca.org (888) 426-4435

Oleanders contain a toxin called Cardenolide Glycosides. The toxin is mostly contained in the sap which is clear to slightly milky colored, and sticky. When ingested in certain quantities, this toxin can cause harm – and death. The extremely bitter and nauseating taste of the sap (much like a rotten lemon) causes a mechanical reflex in the stomach which rejects and expels the vile substance. Although not impossible, a person or animal would have to have a strong stomach or no sense of taste for a dose of the toxin to be fatal.

What can I do to avoid a possible poisoning when working with Oleanders? Wash hands (and arms) thoroughly when finished working with the plant. Do not chew on any part of the plant. And do NOT use it as a skewer for food (or as a toothpick!).

Are the fumes from burning Oleanders hazardous? Yes! The fumes from a burning Oleander are still very hazardous. Avoid the fumes and NEVER use the branches as firewood!

- What do I do if I accidentally ingest some of the sap? Call the poison control center nearest to you.

- What do I do if I see my pet chewing on the plant? Call your veterinarian immediately!

- What do I do if I see my pet chewing on the plant? Call your veterinarian immediately!

- What are some other poisonous plants? Azaleas – Roman soldiers were poisoned from honey of azalea pontica. Rhododendrons – The poisonous compound is Acetylandromedol found in the nectar, and produces depression of blood pressure, shock, and finally death.

Diseases

The Vulnerabilities of Oleander: Common Diseases and Their Management

Oleander (Nerium oleander) is a popular ornamental plant known for its beautiful, fragrant flowers and its ability to thrive in various climates. However, like any plant, oleander is susceptible to a range of diseases that can affect its health and vitality. Understanding these diseases is essential for maintaining healthy plants and ensuring they continue to flourish in gardens and landscapes. This essay explores the most common diseases affecting oleander, their symptoms, causes, and management strategies.

1. Fungal Diseases

a. Leaf Spot Disease

Leaf spot diseases are prevalent among oleander plants and are often caused by various fungal pathogens, including Cercospora and Colletotrichum. Symptoms typically manifest as dark brown or black spots on the leaves, which can lead to premature leaf drop if not addressed. These diseases thrive in humid conditions, making regular monitoring crucial.

Management: To manage leaf spot diseases, gardeners should ensure proper air circulation around the plants and avoid overhead watering. Fungicides may be used to control severe outbreaks, but maintaining overall plant health is the best preventive measure.

b. Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew is characterized by a white, powdery fungus that coats the leaves, stems, and flowers of oleander. It often appears in warm, dry climates, particularly when humidity levels increase. Affected plants may show stunted growth and reduced flowering.

Management: Reducing humidity around the plant, ensuring adequate sunlight, and applying fungicides can help control powdery mildew. Regularly removing affected plant parts is also beneficial.

2. Bacterial Diseases

a. Bacterial Blight

Bacterial blight, caused by Pseudomonas syringae, manifests as water-soaked lesions on the leaves, which can eventually turn brown and lead to leaf drop. The bacteria thrive in wet conditions and can spread rapidly through water splashes or contaminated tools.

Management: To prevent bacterial blight, it is essential to practice good hygiene in the garden, including sterilizing tools and avoiding overhead watering. Infected plants should be removed and destroyed to prevent the spread of the disease.

3. Viral Diseases

a. Oleander Leaf Scorch

Oleander leaf scorch is a viral disease caused by the oleander leaf scorch virus. Symptoms include yellowing leaves, leaf drop, and stunted growth. The virus is spread by sap-sucking insects, such as leafhoppers.

Management: Controlling the insect vectors is crucial in managing oleander leaf scorch. Infected plants should be removed, as there is no cure for the disease once established.

4. Environmental Stressors

While not diseases in the traditional sense, environmental stressors can lead to symptoms that mimic disease. Factors such as nutrient deficiencies, drought, or extreme temperatures can weaken oleander plants, making them more susceptible to infections.

Management: Regularly fertilizing oleander with a balanced fertilizer, ensuring adequate watering during dry spells, and providing protection from extreme temperatures can help mitigate these stressors.

Conclusion

Oleander plants, while hardy and resilient, are not immune to a range of diseases that can impact their growth and appearance. By recognizing the symptoms of common diseases such as fungal infections, bacterial blight, and viral diseases, gardeners can take proactive steps to manage these issues effectively. Maintaining proper cultural practices, such as ensuring good air circulation and avoiding overhead watering, can go a long way in promoting the health of oleander. With diligent care and timely intervention, oleander can continue to thrive and bring beauty to gardens and landscapes.

Freeze Damage

Freeze Damage